Politics

Schengen – the small village that changed Europe

The Schengen Agreement known today was signed in a small village in the south-eastern part of Luxembourg – a place steeped in symbolism

Luxembourg can be crossed by car in just over an hour. Before you know it, you’ll be in nearby France, Germany or Belgium, only the most observant will notice the border sign and the flags of the Grand Duchy far behind.

This possibility is due in part to the country’s small size, but also to a Luxembourgish legacy: a treaty signed 38 years ago in the small village of Schengen in the south-east of the country. The now famous Schengen Agreement has dramatically changed the way we travel in Europe, and it continues to evolve today.

Not so little Luxembourg

At first glance, Luxembourg could be perceived as a commercial center where money is simply made. It takes up very little space on the map and is often inadvertently overlooked as a destination in favor of its neighbors. A founding member of what is now the European Union, this small country is home to one of the EU’s three capitals – Luxembourg (along with Brussels and Strasbourg) – and continues to play a key role in the union’s governance.

The country has the distinction of being a constitutional monarchy situated between the two giant republics of France and Germany, and has paid the price for its location in not one but two world wars, meaning it has plenty of rich and intriguing history to offer. It has a thriving local wine industry, an impressive restaurant scene, countless museums and monuments (from the UNESCO-listed fortress and old town center to the grave of General George Patton Jr.) and a seemingly innate love of seafood, cheese and all things sweet.

In 1985, Luxembourg played an important role in creating a landmark piece of legislation – the signing of the Schengen Agreement – a unilateral agreement guaranteeing border-free travel within European member states.

In the footsteps of this historical place, tourists can travel along the Moselle Valley – a quiet and unpretentious part of the eastern part of Luxembourg. The Moselle River lazily acts as a natural border between Luxembourg and Germany. The valley is clearly central to the country’s winemaking, with vineyards stretching across the low hillsides, broken only by towns and villages scattered across the hills.

On the west bank of the Moselle lies the little Schengen. With roughly 4,000 inhabitants, it’s certainly not the big-name, bright-lights destination one might expect for an agreement that’s changing the way people travel in Europe. Yet it was here, on a gloomy morning on June 14, 1985, that representatives of Belgium, France, Luxembourg, West Germany (then) and the Netherlands gathered to officially sign the agreement for this revolutionary new borderless zone.

The background

The number of European treaties, alliances, cross-alliances and counter-treaties that arose in the second half of the 20th century is mind-boggling. The list screams red tape, but understanding the various alliances at the time is of great importance in creating the Schengen environment.

As World War II drew to a close in 1944, Belgium, Luxembourg and the Netherlands united to create the Benelux. These three countries recognize the benefits that working together will bring in the coming, inevitably difficult decades, and hope to boost trade through a customs agreement.

Based on the Benelux, in 1957 the Treaty of Rome created the European Economic Community (EEC) – an extended customs union of the six founding countries (Benelux and West Germany, France and Italy).

At the beginning of the 1980s, the EEC had 10 member states, and while only fast border checks were in place between them, the reality was that it still held up traffic, required human resources and was increasingly seen as unnecessary bureaucracy. However, the concept of one-way travel without internal borders divides members, with half of them insisting on free movement only for EU citizens and thus remaining committed to internal border checks to distinguish between EU and non-EU citizens EU.

As Martina Kneip, head of the European Schengen Museum, explains: “The idea of open borders in 1985 was something extraordinary – a utopia. No one believed that it could become a reality.”

The remaining five member countries (Benelux, France and West Germany) that wish to carry out the free movement of people and goods are left to initiate the creation of the area to which Schengen will give its name.

Why Schengen?

As Luxembourg takes over the presidency of the EEC, the small country has the right to choose the place where the signing of this treaty takes place. Schengen is the only place where France and Germany share a border with a Benelux country

As a meeting place for three countries, the choice of Schengen is steeped in symbolism. To ensure it was neutral, the signatories gathered aboard the ship MS Princesse Marie-Astrid to write their proposal. The ship is anchored as close as possible to the triple border that runs down the middle of the Moselle River.

Nevertheless, the signing of Schengen failed to attract much support or attention at the time. Apart from the five EEC member states who are against it, many officials, from all countries, simply do not believe it will come into force or succeed. So much so that not a single head of state from the five signatory countries was present on the day of the signing.

From the beginning, the agreement was undervalued, “considered an experiment and something that wouldn’t last,” according to Kneipp. Added to this is the inevitable red tape which ensures that the complete abolition of internal borders in the five founding states will not take place until 1995.

The Schengen area today

Today, the Schengen area consists of 27 member states. Of these, 23 are members of the EU, and four (Iceland, Switzerland, Norway and Liechtenstein) are not.

As then, as now, Schengen has its critics. A migrant crisis has undermined the Schengen idea, giving opponents of open borders plenty of “ammunition” to attack the inclusion efforts put forward by the agreement. Nevertheless, the Schengen area continues to grow, although the accession process remains cumbersome. Policy still determines who can join, as new members must be accepted unanimously. Bulgaria and Romania have repeatedly been vetoed to join Schengen due to concerns about corruption and the security of their external borders.

However, for many the pros of the Schengen area far outweigh the cons. As Kneipp notes: “The Schengen Agreement is something that affects the daily lives of all Schengen member states – around 400 million people.”

What is happening to Schengen itself?

Since Schengen is far from any major thoroughfares, chances are you’ll only end up there if you make a conscious effort to visit. It is about 35 km by car from Luxembourg City and the route goes through forests, farmland and down the Moselle valley. The scenery changes noticeably as you descend the rural hills towards the town of Remich. From here to the epicenter of Schengen – the European Museum – the road is pleasant, winding between the vine-covered slopes and the Moselle River. Here, the story of the creation of the Schengen area is skillfully told through interactive exhibitions and monuments.

Be sure to check out the showcase of official caps of border guards from the member states at the time they joined the area, each demonstrating a national identity sacrificed for the sake of Schengen functioning.

In front of the museum, parts of the Berlin Wall are placed to remind us that walls – in this case the world-famous reinforced concrete wall of one of the founding members of the agreement – do not have to stay in place forever. In front of the museum you will find three stelae or steel plates, each with its own star commemorating the founders. Finally, there are the striking Columns of Nations, which beautifully depict iconic landmarks from each member of the Schengen area.

Of course, there is more than just international law in this peaceful border village. Visitors can extend their stay to enjoy a cruise on the Moselle River, hiking or cycling in the surrounding hills, or try a crémant (the region’s revered white sparkling wine) for a true taste of Schengen life – the little a village whose name will remain forever in history.

Photo credit: consilium.europa.eu

Politics

Estonian Orthodox Church of the Moscow Patriarchate Receives Court Registration

The Estonian Orthodox Church of the Moscow Patriarchate (EOCM) has been granted the right to be called the Estonian Orthodox Church in court. The registration of this name was initially denied and was considered misleading, as this church does not encompass all Orthodox Christians in Estonia.

On March 24, the Tartu District Court upheld the appeal filed on behalf of the Estonian Orthodox Church of the Moscow Patriarchate, and according to the court’s decision, the new name is in accordance with the law and is not misleading regarding the purpose, scope or legal form of the church. This court decision is final and has entered into force.

Estonian Minister of the Interior Lauri Laenemetz initiated a government bill in 2024 that would ban the activities of parishes in Estonia affiliated with organizations that support Russian aggression. According to the minister, these legislative changes are necessary because the Orthodox Church, which is subordinate to the Moscow Patriarchate, is the most important instrument of influence of Russia and the Kremlin in Estonia.

Taras Antoshevsky from the Religious Information Service of Ukraine (RISU) spoke with Ringo Ringvi, an advisor at the Department of Religious Affairs of the Ministry of Internal Affairs of Estonia, about the situation of the Orthodox Church of the Moscow Patriarchate in Estonia.

Politics

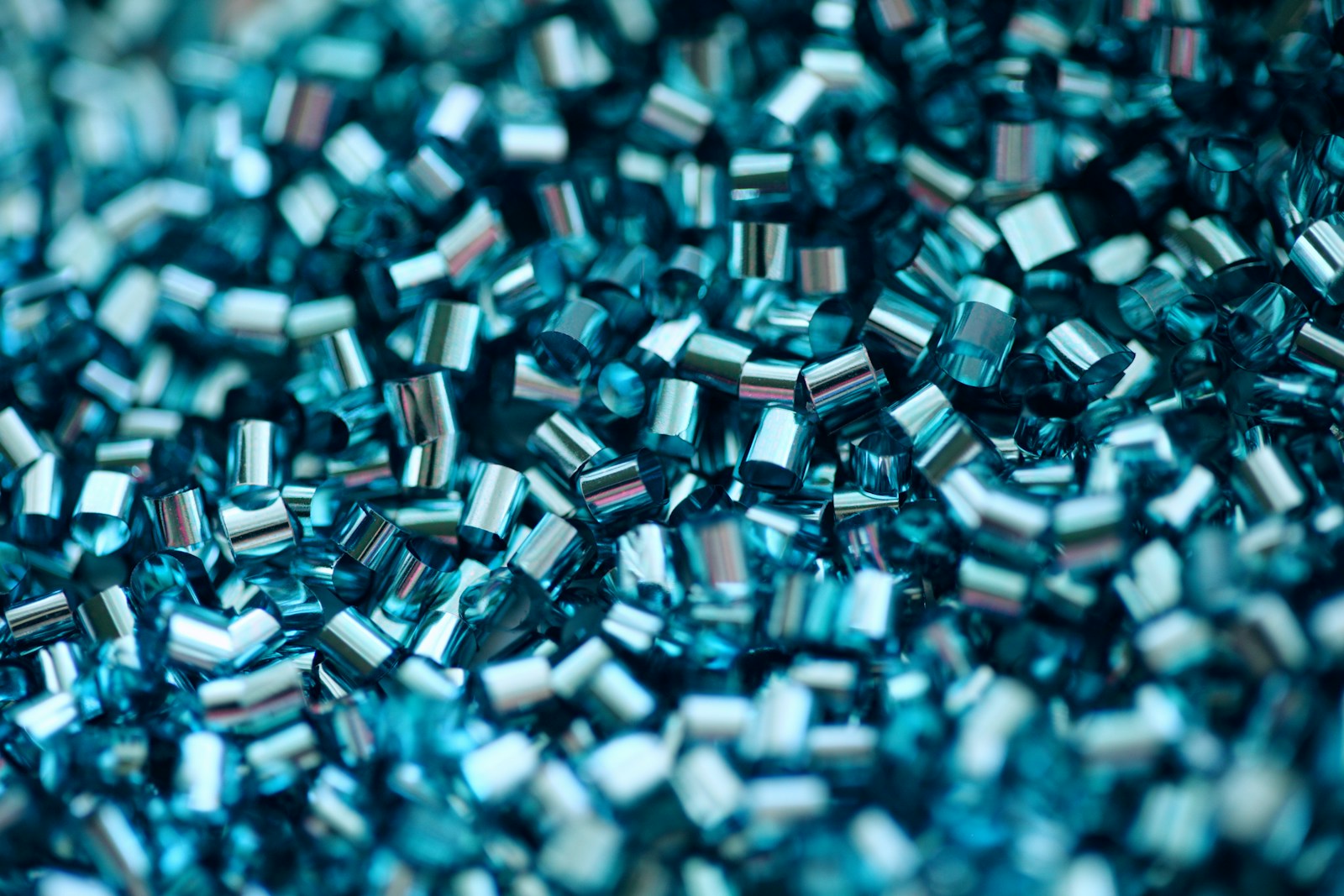

Plastic pellet losses: Council and Parliament agree on new rules to reduce microplastic pollution

Today, the Council and the European Parliament provisionally agreed on a regulation on preventing the loss of plastic pellets – the industrial raw materials used to make plastic products – into the environment. The new rules will help improve the handling of plastic pellets at all stages of the supply chain, both on land and sea.

Microplastics, including plastic pellets are now found everywhere — in our oceans, seas and even in the food we eat. Each year, the equivalent of up to 7,300 truckloads of plastic pellets are lost to the environment. Today, the EU has taken a landmark step toward reducing pellet pollution by adopting measures to tackle losses and ensure correct handling, including in maritime transport.

Paulina Hennig-Kloska, Polish Minister for Climate and Environment

Stronger prevention of pellet losses

Under the new rules, prevention of plastic pellet losses would be the main objective for operators and EU and non-EU carriers. A clear framework sets out obligations for cases of accidental losses focusing on clean-up operations. A clear set of measures will be included in a risk management plan, prepared by each installation handling pellets. Such measures would tackle, among others, packaging, loading and unloading, staff training, as well as necessary equipment.

To provide for a level playing field between the EU and non-EU carriers and to ensure accountability and transparency for all carriers of plastic pellets, non-EU carriers will have to designate an authorised representative in the EU.

Achieving simplification and compliance

In line with the simplification goals for smaller companies and reflecting the Council’s approach, the provisional agreement strikes a balance between a high level of environmental protection and the requirements for companies adapted to their different size. In this sense, operators that handle above 1 500 tonnes of plastic pellets annually will have to obtain a certificate issued by an independent third party. Small companies also handling above 1 500 tonnes per year will benefit from lighter obligations, such as one-off certification to be done in 5 years after the entry into force. Finally, companies handling less than 1 500 tonnes annually and microenterprises will only need to issue a self-declaration of conformity.

Maritime transport

The persistence of a plastic pellet in an aquatic environment can be measured over decades or more, since plastic pellets are not biodegradable. Moreover, maritime transport accounted for around 38% of all pellets transported in the EU in 2022.

Therefore, the co-legislators also agreed to set obligations for the transport of plastic pellets by sea (in freight containers), including ensuring good quality packaging and providing transport and cargo-related information, following the guidelines of the International Maritime Organisation.

Next steps

The provisional agreement will now have to be endorsed by the Council and the Parliament. It will then be formally adopted by both institutions, following a legal and linguistic review, and published in the Official Journal of the EU. The regulation will then become applicable 2 years after publication. To facilitate compliance within the maritime sector, the co-legislators agreed to postpone the application of relevant rules by one year (compared to the rest of the rules set out in the regulation).

Background

It is estimated that between 52 140 and 184 290 tonnes of pellets were lost into the environment in the EU in 2019. Pellet losses can occur at various stages along the value chain. Currently, no EU rules specifically cover plastic pellet losses, despite their adverse impacts on the environment, the climate, the economy and potentially on human health. Plastic pellets rank third among the largest sources of unintentional microplastic releases, after paints and tyres.

Politics

What is your experience with the EU Executive Agencies? Watch out for the survey!

© FRVS+MPCP 2022. The European Times® News is registered as an EU Trademark. All rights reserved. The European Times® and the logo of The European Times® are EU trademarks registered by FRVS+MPCP.

Members/Partners of

About Us

Popular Category

DISCLAIMER OPINIONS: The opinions of the authors or reproduced in the articles are the ones of those stating them and it is their own responsibility. Should you find any incorrections you can always contact the newsdesk to seek a correction or right of replay.

DISCLAIMER TRANSLATIONS: All articles in this site are published in English. The translated versions are done through an automated process known as neural translations. If in doubt, always refer to the original article. Thank you for understanding.

DISCLAIMER PHOTOS: We mostly used photos images that are readily available online, from free sources, or from the people promoting the news. If by any chance it happens that we have used one of your copyrighted photos, please do not hesitate to contact us and we will take it down without question. We do not make profits as this is a not for profit project to give voice to the voiceless while giving them a platform to be informed also of general news, and it is completely free.

Editor Picks

-

Sports6 days ago

Sports6 days agoJannik Sinner, Riccardo Piatti name 4 names for post-Darren Cahill

-

Sports6 days ago

Sports6 days agoLewis Hamilton, disqualification behind: “Immediately looked ahead”

-

Politics6 days ago

Politics6 days ago36 000 free EU travel passes for 18-year-olds

-

Politics6 days ago

Politics6 days agoMSCA awards €608.6 million for doctoral programmes

-

Sports6 days ago

Sports6 days agoMilan, Tammy Abraham sheds light on her future

-

Health & Society6 days ago

Health & Society6 days agoThe Magic of Mushrooms – Exploring Their Nutritional and Healing Powers

-

Politics6 days ago

Politics6 days agoEU launches humanitarian air bridge after Myanmar earthquake

-

Politics4 days ago

Politics4 days ago6 tips to spot and stop information manipulation