Politics

Schengen – the small village that changed Europe

The Schengen Agreement known today was signed in a small village in the south-eastern part of Luxembourg – a place steeped in symbolism

Luxembourg can be crossed by car in just over an hour. Before you know it, you’ll be in nearby France, Germany or Belgium, only the most observant will notice the border sign and the flags of the Grand Duchy far behind.

This possibility is due in part to the country’s small size, but also to a Luxembourgish legacy: a treaty signed 38 years ago in the small village of Schengen in the south-east of the country. The now famous Schengen Agreement has dramatically changed the way we travel in Europe, and it continues to evolve today.

Not so little Luxembourg

At first glance, Luxembourg could be perceived as a commercial center where money is simply made. It takes up very little space on the map and is often inadvertently overlooked as a destination in favor of its neighbors. A founding member of what is now the European Union, this small country is home to one of the EU’s three capitals – Luxembourg (along with Brussels and Strasbourg) – and continues to play a key role in the union’s governance.

The country has the distinction of being a constitutional monarchy situated between the two giant republics of France and Germany, and has paid the price for its location in not one but two world wars, meaning it has plenty of rich and intriguing history to offer. It has a thriving local wine industry, an impressive restaurant scene, countless museums and monuments (from the UNESCO-listed fortress and old town center to the grave of General George Patton Jr.) and a seemingly innate love of seafood, cheese and all things sweet.

In 1985, Luxembourg played an important role in creating a landmark piece of legislation – the signing of the Schengen Agreement – a unilateral agreement guaranteeing border-free travel within European member states.

In the footsteps of this historical place, tourists can travel along the Moselle Valley – a quiet and unpretentious part of the eastern part of Luxembourg. The Moselle River lazily acts as a natural border between Luxembourg and Germany. The valley is clearly central to the country’s winemaking, with vineyards stretching across the low hillsides, broken only by towns and villages scattered across the hills.

On the west bank of the Moselle lies the little Schengen. With roughly 4,000 inhabitants, it’s certainly not the big-name, bright-lights destination one might expect for an agreement that’s changing the way people travel in Europe. Yet it was here, on a gloomy morning on June 14, 1985, that representatives of Belgium, France, Luxembourg, West Germany (then) and the Netherlands gathered to officially sign the agreement for this revolutionary new borderless zone.

The background

The number of European treaties, alliances, cross-alliances and counter-treaties that arose in the second half of the 20th century is mind-boggling. The list screams red tape, but understanding the various alliances at the time is of great importance in creating the Schengen environment.

As World War II drew to a close in 1944, Belgium, Luxembourg and the Netherlands united to create the Benelux. These three countries recognize the benefits that working together will bring in the coming, inevitably difficult decades, and hope to boost trade through a customs agreement.

Based on the Benelux, in 1957 the Treaty of Rome created the European Economic Community (EEC) – an extended customs union of the six founding countries (Benelux and West Germany, France and Italy).

At the beginning of the 1980s, the EEC had 10 member states, and while only fast border checks were in place between them, the reality was that it still held up traffic, required human resources and was increasingly seen as unnecessary bureaucracy. However, the concept of one-way travel without internal borders divides members, with half of them insisting on free movement only for EU citizens and thus remaining committed to internal border checks to distinguish between EU and non-EU citizens EU.

As Martina Kneip, head of the European Schengen Museum, explains: “The idea of open borders in 1985 was something extraordinary – a utopia. No one believed that it could become a reality.”

The remaining five member countries (Benelux, France and West Germany) that wish to carry out the free movement of people and goods are left to initiate the creation of the area to which Schengen will give its name.

Why Schengen?

As Luxembourg takes over the presidency of the EEC, the small country has the right to choose the place where the signing of this treaty takes place. Schengen is the only place where France and Germany share a border with a Benelux country

As a meeting place for three countries, the choice of Schengen is steeped in symbolism. To ensure it was neutral, the signatories gathered aboard the ship MS Princesse Marie-Astrid to write their proposal. The ship is anchored as close as possible to the triple border that runs down the middle of the Moselle River.

Nevertheless, the signing of Schengen failed to attract much support or attention at the time. Apart from the five EEC member states who are against it, many officials, from all countries, simply do not believe it will come into force or succeed. So much so that not a single head of state from the five signatory countries was present on the day of the signing.

From the beginning, the agreement was undervalued, “considered an experiment and something that wouldn’t last,” according to Kneipp. Added to this is the inevitable red tape which ensures that the complete abolition of internal borders in the five founding states will not take place until 1995.

The Schengen area today

Today, the Schengen area consists of 27 member states. Of these, 23 are members of the EU, and four (Iceland, Switzerland, Norway and Liechtenstein) are not.

As then, as now, Schengen has its critics. A migrant crisis has undermined the Schengen idea, giving opponents of open borders plenty of “ammunition” to attack the inclusion efforts put forward by the agreement. Nevertheless, the Schengen area continues to grow, although the accession process remains cumbersome. Policy still determines who can join, as new members must be accepted unanimously. Bulgaria and Romania have repeatedly been vetoed to join Schengen due to concerns about corruption and the security of their external borders.

However, for many the pros of the Schengen area far outweigh the cons. As Kneipp notes: “The Schengen Agreement is something that affects the daily lives of all Schengen member states – around 400 million people.”

What is happening to Schengen itself?

Since Schengen is far from any major thoroughfares, chances are you’ll only end up there if you make a conscious effort to visit. It is about 35 km by car from Luxembourg City and the route goes through forests, farmland and down the Moselle valley. The scenery changes noticeably as you descend the rural hills towards the town of Remich. From here to the epicenter of Schengen – the European Museum – the road is pleasant, winding between the vine-covered slopes and the Moselle River. Here, the story of the creation of the Schengen area is skillfully told through interactive exhibitions and monuments.

Be sure to check out the showcase of official caps of border guards from the member states at the time they joined the area, each demonstrating a national identity sacrificed for the sake of Schengen functioning.

In front of the museum, parts of the Berlin Wall are placed to remind us that walls – in this case the world-famous reinforced concrete wall of one of the founding members of the agreement – do not have to stay in place forever. In front of the museum you will find three stelae or steel plates, each with its own star commemorating the founders. Finally, there are the striking Columns of Nations, which beautifully depict iconic landmarks from each member of the Schengen area.

Of course, there is more than just international law in this peaceful border village. Visitors can extend their stay to enjoy a cruise on the Moselle River, hiking or cycling in the surrounding hills, or try a crémant (the region’s revered white sparkling wine) for a true taste of Schengen life – the little a village whose name will remain forever in history.

Photo credit: consilium.europa.eu

Politics

European Parliament begins its 10th term

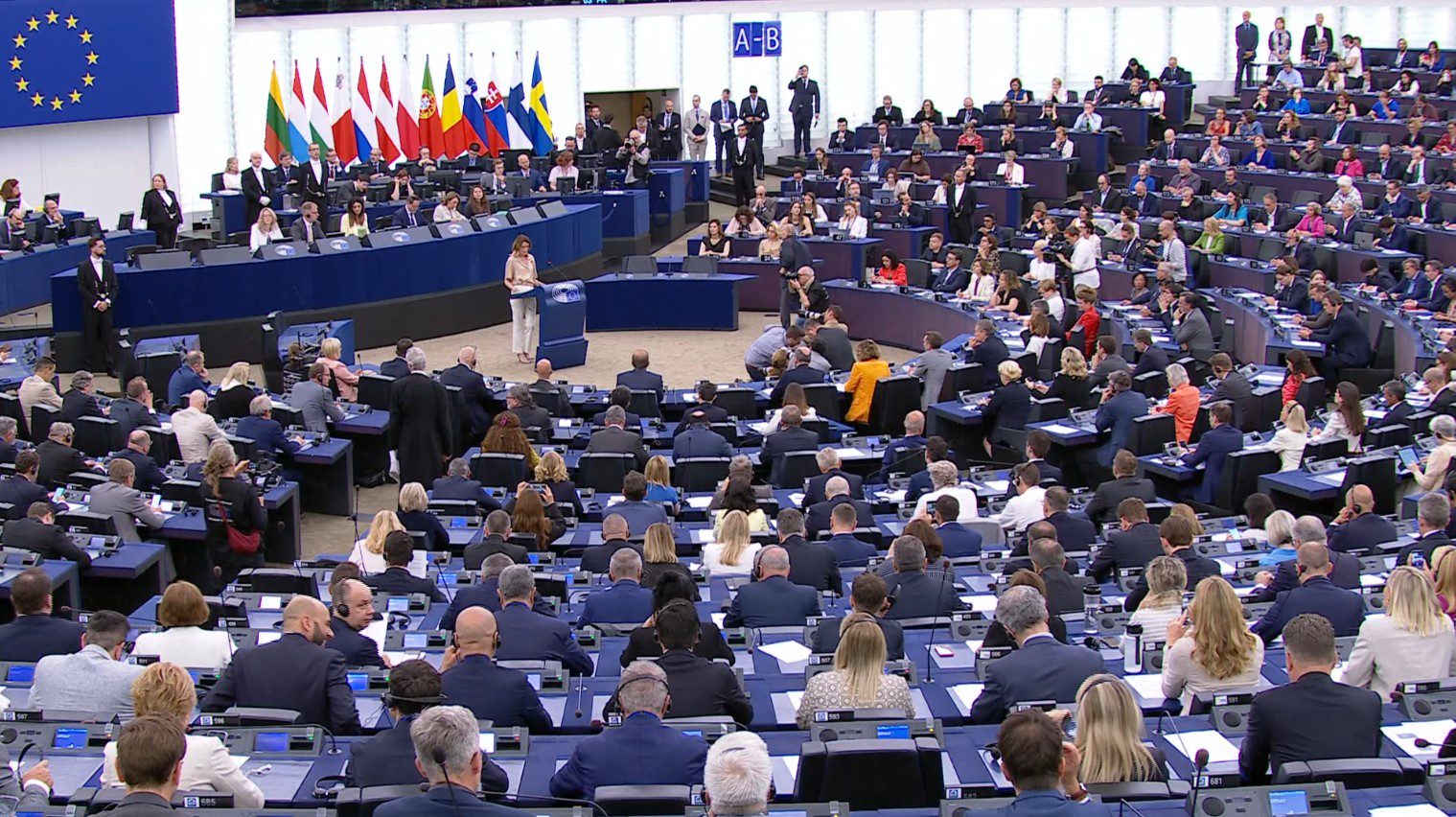

European Parliament Convenes in Strasbourg: New President to be Elected amid Growing Diversity

On a momentous Tuesday in Strasbourg, the European Parliament, following the recent European elections held on 6-9 June, officially commenced its proceedings. The session, presided over by the outgoing EP President, Roberta Metsola of the EPP from Malta, commenced with a musical interlude before Pina Picierno, the second Vice-President in the outgoing Parliament from Italy’s S&D, announced the contenders for the coveted Presidency of the Parliament.

The highly anticipated vote, conducted through a secret paper ballot, is set to occur immediately after the inaugural session. To ensure a fair process, eight MEPs, selected by lot, will oversee the election proceedings.

The distinguished candidates vying for the Presidency are Roberta Metsola representing EPP from Malta and Irene Montero from The Left in Spain. Ahead of the crucial vote, both candidates delivered succinct statements to the plenary, outlining their visions for the future of the European Parliament.

To attain victory, a candidate must secure an absolute majority of valid votes cast, which equates to 50% plus one. In the event of no clear winner in the initial round of voting, subsequent rounds may follow with the possibility of new or existing candidates being nominated under the same stipulations. If needed, a third round could ensue with the same regulations. Should no candidate emerge victorious after the third round, the two candidates with the highest votes in this round will advance to a decisive fourth and final round, with the majority winner emerging triumphant.

Upon the election of the new President, the distinguished individual will assume the leadership position and deliver a notable opening address, setting the tone for the parliamentary term ahead.

In this landmark tenth term, the European Parliament boasts 720 seats, an increase of 15 from the previous legislature. Notably, 54% of MEPs are fresh faces, marking a slight decrease from the 2019 intake of 61%, with the representation of women comprising 39%, down marginally from the 40% mark in 2019.

Among the diverse MEP cohort, Lena Schilling, a 23-year-old from Austria representing Greens/EFA, stands as the youngest member, while the seasoned Leoluca Orlando from Italy, a Green/EFA representative aged 77, holds the distinction of the oldest MEP. The average age of MEPs stands at 50, reflecting a diverse range of experiences and perspectives within the parliamentary body.

As the tenth term commences, the European Parliament encompasses eight political groups, an increase from the previous session. Additionally, 32 MEPs remain non-attached, underscoring the dynamic landscape of political affiliations within the Parliament and highlighting the vibrant tapestry of representation in the European legislative body.

Politics

For the first time in 40 years, the Olympics will not be broadcast in Russia

Not a single TV channel, streaming platform or cinema in Russia will show the competitions from the Summer Olympics in Paris, which begin on July 26, sports.ru writes. This happened for the first time in 40 years, when in 1984 the USSR boycotted the Olympics in Los Angeles.

The official explanation is that this time only 16 athletes will participate under a neutral flag, without an anthem and in “unpopular sports”. The unofficial thing is that this is a purely political decision of the Kremlin, and heads of federations call those who agreed to participate traitors, homeless people and foreign agents.

Paris Mayor on Russians at the 2024 Olympics: It would be better if they didn’t come

Anne Hidalgo condemned the International Olympic Committee’s decision regarding representatives of the aggressor country, she said already in March.

According to the official, it would be good if athletes from the terrorist country did not participate in international competitions.

“I prefer that they not come. We cannot act as if the invasion does not exist. We cannot act as if Putin is not a dictator who is threatening all of Europe today.”

At the same time, she added that such sanctions cannot be imposed against Israeli athletes, since Israel’s actions are different from Russia’s aggression.

“There can be no talk of imposing sanctions against Israel in connection with the Olympic and Paralympic Games. Because Israel is a democratic country,” the mayor told Reuters.

Photo: Social Network / korrespondent.net.

Politics

Keir Starmer Secures Historic Labour Victory, Ending 14 Years of Conservative Rule in UK

London – In a seismic shift in British politics, the Labour Party, led by Keir Starmer, has achieved a resounding victory in the UK general election, bringing an end to 14 years of Conservative governance. The results, which had been foreshadowed by months of polling, have given Labour its strongest parliamentary majority since 2001.

Labour secured an impressive 412 seats, far surpassing the 326 required for an absolute majority and more than doubling their 2019 performance. This landslide victory marks a dramatic turnaround for the party and signals a clear desire for change among the British electorate.

Upon learning of his victory in his central London constituency, Starmer declared, “The people have spoken, and they are ready for change.” This statement encapsulates the mood of a nation seemingly eager to embark on a new political chapter.

The Conservative Party, in stark contrast, suffered its worst defeat since its founding in 1834. The Tories lost at least 250 seats compared to their 2019 performance under Boris Johnson, ending up with a mere 121 seats. This historic collapse prompted the outgoing Prime Minister, Rishi Sunak, to apologize to “those Conservatives who have lost despite their dedication” while congratulating Starmer on his victory.

The election also saw significant shifts for other parties. The Liberal Democrats, led by Ed Davey, emerged as the third-largest party with 71 seats, a gain of 63 from the previous election. The Scottish National Party (SNP) experienced a dramatic decline, securing only nine seats, a loss of 38 compared to 2019. Sinn Fein, the Irish republican party, maintained its seven seats.

In a surprising development, the nationalist-populist Reform UK, led by Nigel Farage, entered Parliament with four seats, exceeding all poll predictions. The Green Party quadrupled its representation, winning four seats in total.

Starmer’s first address as Prime Minister was filled with promises of change and renewal. “We did it!” he exclaimed, emphasizing that Britons would wake up to find “a weight has finally been lifted from the shoulders of this great nation.” He stressed the urgency of rebuilding trust in politics and committed to serving all citizens, regardless of their voting preferences.

The new Prime Minister outlined his government’s priorities, including improving security on streets and borders, rebuilding infrastructure, and enhancing opportunities in education and employment. “Changing a country isn’t as easy as pressing a button,” Starmer cautioned, “We will rebuild the United Kingdom, brick by brick.”

Rishi Sunak, in his farewell speech, acknowledged the clear signal for change sent by the electorate. “I have heard your anger and disappointment. I take responsibility for these results,” he stated. Sunak announced his intention to step down as Conservative Party leader, but not immediately, allowing time for a formal process to choose his successor.

The election also marked a personal triumph for Nigel Farage, who finally won a parliamentary seat on his eighth attempt, representing Clacton-on-Sea. Farage hailed his party’s performance as “extraordinary” and vowed to fill what he sees as a “huge void in the center-right.”

In regional developments, Sinn Fein became the largest Northern Irish party in the British Parliament for the first time, maintaining its seven seats while the Democratic Unionist Party (DUP) fell to four. In Scotland, the SNP lost its dominance, dropping from 48 seats in 2019 to just 8, with Labour making significant gains. Wales saw the Conservatives lose all representation, with Labour dominating the results.

As the United Kingdom enters this new political era under Starmer’s leadership, the country faces significant challenges. The incoming government must address economic concerns, social policies, and perhaps most critically, work to restore public trust in the political system. The scale of Labour’s victory suggests a strong mandate for change, but the real test lies in translating this electoral success into effective governance in the years to come.

-

Sports6 days ago

Sports6 days agoOfficial: Juventus announces sixth purchase

-

Health & Society6 days ago

Health & Society6 days agoThe intoxicated society

-

Health & Society2 days ago

Health & Society2 days ago7 Superfoods That Will Boost Your Fitness Results

-

Politics4 days ago

Politics4 days agoThe Russian patriarch to Putin: You are the first truly Orthodox president

-

Sports5 days ago

Sports5 days agoBeautiful Juve: Vlahovic and youth rout Verona. Thiago Motta first

-

Sports5 days ago

Sports5 days agoJuventus, Vlahovic: “Now we play a different game.”

-

EU & the World3 days ago

EU & the World3 days agoGrier Henchy Wears Mom Brooke Shields’ 1997 Wedding Dress to HS Graduation

-

Travel1 day ago

Venice 2024 review: ‘Babygirl’ – Nicole Kidman shines in sex-positive BDSM drama